Well, it wasn’t so very long ago – only about twenty-three years.

I was foreman of a factory, and he lived a thousand miles away, at Missouri Valley, Iowa. I was twenty-four, and he was fourteen. His brother was traveling for the Firm, and one day this brother showed me a letter from the lad in Missouri Valley. The missive was so painstaking, so exact, and revealed the soul of the child so vividly, that I laughed aloud – a laugh that died away to a sigh.

The boy was beating his wings against the bars – the bars of Missouri Valley – he wanted opportunity.

And all he got was unending toil, dead monotony, stupid misunderstanding, and com bread and molasses.

There wasn’t love enough in Missouri Valley to go ’round-that was plain. The boy’s mother had been of the Nancy Hanks type – worn, yellow and sad – and had given up the fight and been left to sleep her long sleep in a prairie grave on one of the many migrations. The father’s ambition had got stuck in the mud, and under the tongue-lash of a strident, strenuous, gee-haw consort, he had run up the white flag.

The boy wanted to come East.

It was a dubious investment-a sort of financial plunge, a blind pool-to send for this buckwheat midget. The fare was thirty~three dollars and fifty cents.

The proprietor, a cautious man, said that the boy wasn’t worth the money. There were plenty of boys – the alleys swarmed with them.

So there the matter rested.

But the lad in Missouri Valley didn’t let it rest long. He had been informed that we did not consider him worth thirty-three dollars and fifty cents, so he offered to split the difference. He would come for half-he could ride on half fare – the Railroad Agent at Missouri Valley said that if he bought a half-fare ticket, got on a train, and explained to the conductor and everybody that he was ‘leven, goin’ on twelve, and stuck to it, it would be all right; and he would not expect any wages until he had paid us back. He had no money of his own, all he earned was taken from him by the kind folks with whom he lived, and would be until noon of the day he was twenty-one years old.

Did we want to invest sixteen dollars and seventy-five cents in him?

We waxed reckless and sent the money – more than that, we sent a twenty-dollar bill. We plunged!

In just a week the investment arrived. He did not advise when he would come, or how. He came, we saw, he conquered. Why should he advise of his coming? He just reported, and his first words were the Duke’s motto: “I am here.”

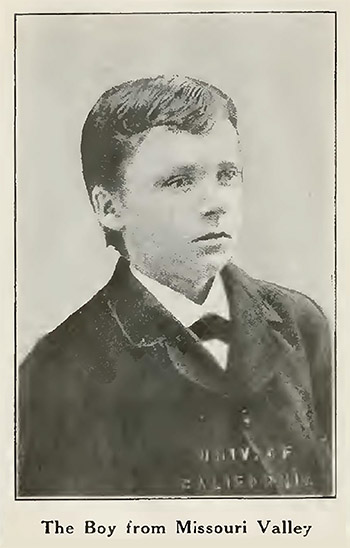

He was unnecessarily freckled and curiously small.

His legs had the Greek curve, from much horseback riding, herding cattle on the prairies; his hair was the color of a Tamworth pig; his hands were red; his wrists bony and briar-scarred. He carried his shoes in his hands, so as not to wear out the sidewalk, or because they aggravated sundry stonebruises – I don’t know which.

“I am here!” said the lad, and he planked down on the desk three dollars and twenty-five cents.

It was the change from the twenty-dollar bill.

“Didn’t you have to spend any money on the way here?” I asked.

“No, I had all I wanted to eat,” he replied, and pointed to a basket that sat on the floor.

I called in the Proprietor, and we looked the lad over. We walked around him twice, gazed at each other, and adjourned to the hallway for consultation.

The boy was not big enough to do a man’s work, and if we set him to work in the factory with the city boys, they would surely pick on him and make life for him very uncomfortable. He had a half-sad and winsome look that had won from our hard hearts something akin to pity. He was so innocent, so full of faith, and we saw at a glance that he had been overworked, underfed – at least misfed – and underloved. He was different from other boys – and in spite of the grime of travel, and the freckles, he was pretty as a groundsquirrel.

His faith made him whole: he won us.

But why had we brought him to the miserable and dirty city – this grim place of disillusionment!

”He might index the letter-book?” I ventured.

“That’s it, yes, let him index the letter-book.”

So I went back and got the letter-book. But the boy’s head only came to the top of the standup desk, and when he reached for the letter-book on the desk he had to grope for it. I gave him my high-stool, but this was too low.

“I know what to do,” he said. Through the window that looked from the office to the shipping room, he had spied a pile of boxes. “I know what to do!”

In a minute he had placed two boxes end to end, nailed them together, clinched the nails, and carried his improvised high-stool into the office.

“I know what to do!”

And he usually did; and does yet.

We found him a boarding place with a worthy widow whose children had all grown big and flown. Her house was empty, and so was her mother-heart: she was like that old woman in Rab, who was placed on the surgeon’s table and given chloroform, and who held to her breast an imaginary child, and crooned a lullaby to a babe, dead thirty years before.

So the boy boarded with the widow and worked in the office.

He indexed the letter-book – he indexed everything.

And then he filed everything – letters, bills, circulars. He stamped the letters going out, swept the office, and dusted things that had never been dusted before. He was orderly, alert, active, cheerful, and the Proprietor said to me one day,

“I wonder how we ever got along without that boy from Missouri Valley.”

Six months had passed, and there came a day when one of the workmen intimated to the Proprietor that he better look out for that red-headed office boy.

Of course, the Proprietor insisted on hearing the rest, and the man then explained that almost every night the boy came back to the office. He had seen him. The boy had a tin box and letterbooksnin it, and papers, and the Lord knows what not!

Watch him! The Proprietor advised with me because I was astute – at least he thought I was, and I agreed with him.

He thought Jabesh was at the bottom of it.

Jabesh was our chief competitor. Jabesh had hired away two of our men, and we had gotten three of his. “Jabe,” we called him in derision – Jabe had gotten into the factory twice on pretense of seeing a man who wanted to join the Epworth League, or Something. We had ordered him out, because we knew he was trying to steal our “process.” Jabe was a rogue-that was sure.

Worse than that, Jabe was a Methodist. The Proprietor was a Baptist, and regarded all Methodists with a prenatal aversion that swung between fear and contempt. The mere thought of Jabe gave us gooseflesh. Jabesh was the bugaboo that haunted our dreams. Our chief worry was that we would never be able to save our Bank Balance alive, for fear o’ Jabe.

“That tamashun Jabe has hired our office boy to give him a list of our customers-he is stealing our formulas, I know,” said the Proprietor. “The cub’s pretense of wanting a key to the factory so he could sweep out early, was really that he might get in late.”

Next day we watched the office boy. He surely looked guilty – his freckles stood out like sunspots, and he was more bow-legged than ever.

The workman who had given the clue, on being further interrogated, was sure he had seen Jabe go by the factory twice in one evening.

That settled it.

At eight o’clock that night we went down to the factory. It was a full mile, and in an “objectionable” part of the town.

There was a dim light in the office. We peered through the windows, and sure enough, there was the boy hard at work writing. There were several books before him, a tin box and some papers. We waited and watched him copy something into a letter-book.

We withdrew and consulted. To confront the culprit then and there seemed the proper thing.

We unlocked the door and walked softly in.

The boy was startled by our approach, and still more by our manner. When the Proprietor demanded the letter that he had just written, he began to cry, and then we knew we had him.

The Proprietor took the letter and read it. It was to Jimmy Smith in Missouri Valley. It told all about how the writer was getting on, about the good woman he boarded with, and it told all about me and about the Proprietor. It pictured us as models of virtue, excellence and truth.

But we were not to be put off thus. We examined the letter-book, and alas! it was filled only with news letters to sundry cousins and aunts.

Then we dived to the bottom of the tin box, still in search of things contraband. All we found was a little old Bible, a diary, and some trinkets in the way of lace and a ribbon that had once been the property of the dead Nancy Hanks.

Then we found a Savings-Bank Book, and by the entries saw that the boy had deposited one dollar every Monday morning for eleven weeks. He had been with us for six months, and his pay was two dollars a week and board – we wondered what he had done with the rest!

We questioned the offender at length. The boy averred that he came to the office evenings only because he wanted to write letters and get his ‘rithmetic lesson. He would not think of writing his personal letters on our time, and the only reason he wanted to write at the office instead of at home, was so he could use the letter-press. He wanted to copy all of his letters-one should be business-like in all things.

The Proprietor coughed and warned the boy never to let it happen again.We started for home, walking silently but very fast.

The stillness was only broken once, when the Proprietor said: “That consamed Jabe ! If ever I find him around our factory, I’ll tweak his nincompoop nose, that’s what I will do.”

Twenty-three years ! That factory has grown to be the biggest of its kind in America. The redhaired boy from Missouri Valley is its manager.

Emerson says, “Every great institution is the lengthened shadow of a single man.”

The Savings-Bank Habit came naturally to that boy from Missouri Valley. In a year he was getting six dollars and board, and he deposited four dollars every Monday. In three years this had increased to ten, and some years after, when he became a partner, he had his limit in The Bank.

The Savings-Bank Habit is not so bad as the Cab Habit – nor so costly to your thinkery and wallet as the Cigarette Habit.

I have been wage-earner, foreman and employer. I have had a thousand men on my pay-roll at a time, and I ‘II tell you this : The man with the Savings-Bank Habit is the one who never gets laid off: he’s the one who can get along without you, but you cannot get along without him. The Savings-Bank Habit means sound sleep, good digestion, cool judgment and manly independence.

The most healthful thing I know of is a SavingsBankBook – there are no microbes in it to steal away your peace of mind. It is a guarantee of good behavior.

The Missouri Valley boy gets twenty-five thousand a year, they say. It is none too much. Such masterly men are rare; Rockefeller says he has vacancies for eight now, with salaries no object, if they can do the work. (That business grew because the boy from Missouri Valley grew with it, and he grew because the business grew. Which is a free paraphrase from Macaulay, who said that Horace Walpole influenced his age because he was influenced by his age.

Jabesh has gone on his Long Occasion, discouraged and whipped by an unappreciative world.

Jabe never acquired the Savings-Bank Habit. If he had had the gumption to discover a red-haired boy from Missouri Valley, he might now be sporting an automobile on Delaware Avenue instead of being in Abraham’s Bosom.

We shall all be in Abraham’s Bosom day after tomorrow; and then I ‘II explain to Jabesh that no man ever succeeded in a masterly way, excepting as he got level-headed men with the Savings-Bank Habit to do his work. Blessed is that man who has found somebody to do his work.

There is plenty of iron pyrites, but the Proprietor and I know Pay Gravel when we see it.

I guess so!

Elbert Hubbard, (1904)

.